Un reportage EQDA

Basel, Switzerland: In the last four years, three new mothers have made the long winding walk from Olten railway station or bus stand to the local hospital – the Kantonsspital Olten.

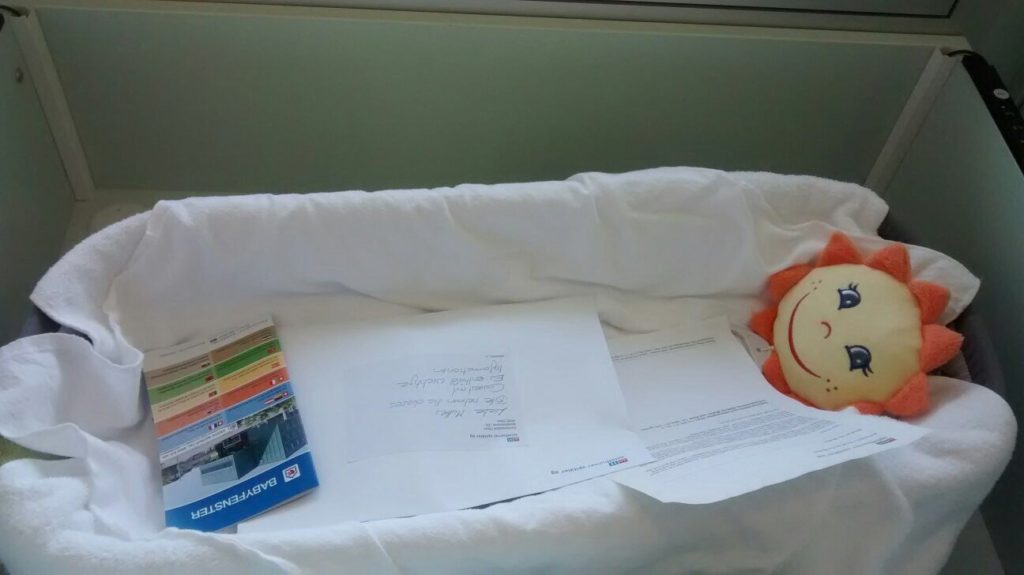

A small, slightly-hidden alcove at the centre of the hospital’s sprawling garden grounds is their eventual destination, where they will give up their newborn children and place them into a window hatch. Once done, the women have three minutes to make a quick exit before an alarm blares, alerting the hospital authorities to the baby’s presence.

The Olten baby hatch, or baby box, is one among two hundred such across Europe (eight in Switzerland alone) in countries including Italy, Germany, Belgium and Austria.

These boxes are modelled after an artefact of medieval times – the foundling wheel. In 1198, Pope Innocent III decreed that wheels should be set up outside churches so that mothers could leave their children in secret instead of killing them, a practice that was apparently common at the time.

The modern version comes with better technology, but the general principle is the same.

“In many cases, it is the last opportunity to save the child’s life. Whatever the mother’s reason for abandoning her child may have been, the box represents a last attempt making sure the baby is not abandoned in a place where it will die,” says Franz Schwaller, the Swiss-German director of Olten Hospital.

A secure, often government-funded location to drop off unwanted babies isn’t a Western phenomenon. Across Asia, even in India, the idea is attractive and seen as a method of battling infanticide in general and female foeticide in particular.

In 2015, the Rajasthan state government introduced the Ashra Palna Yojana programme, which has set up 65 cradles across state and district hospitals, where parents can anonymously drop off their babies. « The main aim of the scheme is to save the newborn babies who are dumped in dustbins and bushes right after birth, most of whom happen to be girls, »Devendra Agrawal, health department adviser of the scheme, told Al Jazeera.

Religion versus gender justice

It is surprising therefore that the baby box – a seemingly simple device that helps reinforce the rights of women and mothers – is a matter of bitter debate in Switzerland and other European countries.

There are are legal issues to be sure. In Amsterdam for instance, plans to open a hatch in 2003 were put to an end after heavy protests over the legality of such an option, a reflection of the debate over whether baby hatches violate a child’s right to know the identity of her parents.

In Switzerland, however, the debate is more fundamental. One of the country’s most outspoken sexual rights organisations – the Sexuelle Gesundheit, Switzerland’s version of Planned Parenthood and a vocal supporter of abortion rights – is vehemently opposed to the idea of baby hatches.

Christine Seiber, a senior official with the organisation,is quick to rattle off the smaller and more practical problems with the boxes – they often affect the health of the woman (baby boxes encourage more women to engage in home-births). It’s also unclear whether it is truly the woman who is giving up the child. Seiber points out that it could be the abusive boyfriend, father or family that is behind the decision.

“It’s also a question of numbers. Why does Switzerland have 8 baby boxes, when there’s not that much need,” Seiber asks.

It’s here that the numbers are indeed slightly puzzling. Switzerland as a country has one of the lowest rates of teenage pregnancy and abortions across Europe – roughly 6.8 per thousand women aged between 15 and 44 at last count. This is in comparison to countries such as Finland or Germany which have historically had higher infanticide and abortion rates.

This is where the true ideological problem starts.

Switzerland’s drive for baby boxes – unlike most European countries – is not a result of government-oriented and state-funded programmes, but rather the efforts of a private organisation. A staunchly anti-abortion, non-profit foundation called Swiss Aid for Mother and Child (SAMC) to be precise.

Over the last fifteen years (the first Swiss baby box was set up in 2001) SAMC has personally financed the majority of the hatches that have been set up at various hospitals across the country. Sexuelle Gesundheit and most women-rights organisations in Switzerland are deeply suspicious of SAMC and its motives.

“What we realised in 2012 is that in several places there was a huge discussion about these baby boxes. We realised that several hospitals were about to open these boxes. And that the partner that had collaborated with those hospitals was SAMC,” Susanne Rohner Baumgartner, an advocacy officer at Sexuelle Gesundheit, says.

Baumgartner doesn’t mince words when it comes to SAMC’s actions over the past few years.

“They are, in my view, an extreme anti-choice organisation. They have backed legislative initiatives that wanted to ban abortion. And their positions are extreme as well. No abortion even after rape for instance,” she says.

That the rise of baby boxes in Switzerland is indeed political becomes clearer when looking at a broad timeline.

Until June 2010, the country had only one such facility, which was located in Einsiedeln. By 2017 there were eight boxes even though there was nothing to suggest that the demand or need for the hatches had gone up. So, what happened in the intervening years?

For one, in 2011-2012, a successful movement and petition drive by pro-life and anti-abortion groups kicked off a legal process that forced the Swiss government hold a national referendum in 2014 on whether abortions should stop being publicly funded. In 2002, the country had legalised abortion through a similar referendum.

“It’s a partial victory that the anti-abortion militants won yesterday, in registering their federal initiative,” journalist Benito Perez wrote in 2011 in Switzerland’s Le Courrier newspaper. “Nine years after the plebiscite for decriminalization (72% voting yes), one could expect that there would not be 100,000 citizens to lead a rearguard action. This disproof should act as a warning and a call to mobilization.”

While the 2014 referendum, which would have dropped abortion coverage from public health insurance was defeated by a large margin, it has left many Swiss women’s rights organisations unhappy with SAMC and perhaps prejudiced against how baby boxes have become a symbol of the pro-life movement.

This anger and mistrust also extends to how Swiss Aid for Mother and Child allegedly operates. In addition to funding the baby boxes, the organisation also extends help to mothers in distress, both financially and through social counselling. Their helpline and phone counselling services are popular, helping 5-10 expecting mothers every day.

A 2014 investigation by German news organisation Die Zeit, however, alleged that SAMC’s services were sharply skewed towards steering away pregnant women from abortions. Going undercover, the Die Zeit journalist allegedly showed that SAMC’s counselling services often disparage and shame women into having their babies and giving them away for adoption instead.

Sexuelle Gesundheit’s Baumgartner is more blunt. “Read the Die Zeit article. Their helplines brainwash women,” she says.

For Dominik Müggler, the founder and president of Swiss Aid for Mother and Child, the baby boxes represent only a starting (if highly public) point for his organisation.

“The purpose of this organisation is to render aid to mothers, to families, in distress. We are quite clear. Our goal is not to help a family if there is a divorce or alcoholism, though we often end up doing so, but the important condition is that the distress must go back to the existence of a child,” he says.

Müggler, a thin bespectacled Swiss-German man, has no illusions as to what his foundation offers that the Swiss state doesn’t.

“The state often has political conditions. If a girl or woman who is also a student becomes pregnant, the state does not help. It says stop your studies and start working and then you can make money. Or it says if you don’t have money to support the child, get an abortion. But we say okay this student has a problem. We give her money so that she can continue her studies for example,” the SAMC president says.

With an operating budget of over three million Swiss francs in 2016, SAMC primarily functions through a helpline, a counselling call centre and a physical location.

Dominik Müggler (right), president of SAMC, at his organisation’s office just outside Basel. Credit: SwissInfo.ch

When distressed women call, the organisation’s team of 17 professional counsellors talk them through the problem. In certain cases they pay for the mother’s train ticket to come out to their office. “Many things we can do over the phone or by email. We send [the mothers] clothes, diapers. Other times, it’s more serious and we offer greater financial support for giving birth in a hospital in a city that is away from their own,” Müggler says.

The idea behind SAMC and baby boxes comes from two incidents that affected Müggler.

The first is deeply personal. An economics and political science graduate, Müggler started his career out in Switzerland’s pharmaceutical industry. At the time, his wife became pregnant with a baby whose likelihood of being born handicapped or with a birth defect was high.

“We asked the doctor and he said yes you can abort. We said we do not want to have an abortion. If the baby has some health problem, we shouldn’t kill him but give him the love and care that he needs. However, when my wife gave birth, the baby died. He died in my arms 19 hours after being born.”

Müggler explains that it was around that time that he “began to think about the political campaign for or against abortion.” He says wanting to help children and ladies who had problems stemmed from both his “Christian faith as well as a natural reaction to what happened to his own child”.

Upon some prodding, he and his fellow employees are quick to add that their organisation “doesn’t condemn or shame” women who opt for abortions but are merely against the act of abortion only.

The second incident more directly helped the process of setting up baby boxes. In 2001, Müggler met with the director of the Einsiedeln hospital where the first baby hatch was eventually constructed.

“When I got there, the management told me that they had already decided on opening one. The reason behind it was that in the Zurich area a year later, the local populace was shocked when they found that a woman had abandoned her child on the bank of a lake in the countryside. The child had had died due to the cold, due to hypothermia. The village and hospital was shocked and wanted to do whatever could be done to prevent another case like this,” Müggler says.

For six out of Switzerland’s eight baby hatches, SAMC has funded the cost of setting up a baby hatch in each canton’s (district government) hospital, which ranges between 6000 and 8000 Swiss francs (around Rs 40 lakh).

In certain cases, the organisation also pays for the cost of fostering a child for 12 months – Swiss mothers are allowed to change their mind up to 1 year after placing their child in a baby hatch – before it is sent for official adoption.

Müggler acknowledges that there were legal battles in the initial days of setting up the baby boxes, with critics saying that it provided “unnecessary publicity or a way for mothers to get rid of their child and responsibility.”

To harsher criticisms such as the Die Zeit article, SAMC’s employees and Müggler respond in equal measure.

“You need to know that the journalist who wrote that article was against the opening of the baby box in Olten. We believe she wrote that article out of revenge. I was astonished that she played a mother in distress and lied about how we offer counselling services,” he says.

Müggler’s logic is simple: “We only want to save the life of the children and to prevent the mothers from feeling guilty.”

In interviews with The Wire, SAMC employees stressed that the organisation was called Swiss Aid for Mother *and* Child. “The ‘and’ is very important. It is the policy of our organisation,” Müggler says.

To a certain extent, his organisation is structured in this manner. When asked, Müggler admits that SAMC would not offer financial help to women who wanted to opt for an abortion and states that his organisation’s donors would not be pleased.

“Many of the people who fund us are women for instance who went through an abortion and find themselves grief-struck later. They know what our goal is and support us in this.”

Baby boxes and hatches also come with legal issues. In 2012, Maria Herczog, a member of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child committee, stated that such devices would violate the right of the child to trace her identity.

“Just like medieval times, in many countries we see people claiming that baby boxes prevent infanticide… there is no evidence for this,” said Herczog.

In Switzerland, this issue is looked at more liberally. Olten Hospital director Franz Schwaller says that in his perspective, the right of a child’s life trumps the right to knowledge.

“When it comes to the pro and anti-abortion debate here in Switzerland, we stay out of it and are neutral. We follow the law which of course makes abortions legal. However, we believe that first the child needs to live in order to identify her parents,” Schwaller says.

An alternative to baby boxes which has seen some traction, is the concept of confidential births. This is where the pregnant would come in, perhaps sometimes before the due date or even when is about to give birth, and the hospital would not officially record the birth but would note the identity of the woman.

This option, reproductive rights organisations like Sexuelle Gesundheit and Swiss hospitals say, provides the best of both worlds.

“The woman is able to receive the adequate medical care she might need after giving birth and the child gets to know after he or she turns 18 the identity of his or her mother,” says Schwaller.

Confidential births, however, haven’t taken off in Switzerland or Europe. SAMC and Müggler claim that it’s because the process is flawed with confidential births “sometimes not really being confidential.”

Legal experts note that the process of adopting is much harder in a confidential birth – new mothers have to wait up to 12 weeks sometimes to officially give up the baby for adoption, which involves having the mother stick around and engage in much paper-work.

“The basic idea is that when a mother wants to go for a confidential birth, there can’t be too effort in it. Otherwise it negates the very need, whatever it may be, for confidentiality. I know of one case where we had to get a woman’s confidential birth case shifted because her father worked in the local authorities from which she would have had to get a document signed for adoption! Obviously she didn’t want her father to know about the baby. Until this is resolved, we will need baby boxes,” says Müggler