While Switzerland has the capacity to monitor glacier hazards, many countries do not, including Indonesia, whose Carstensz Glacier in Papua is among the most at risk.

Radhiyya Indra /The Jakarta Post

Serene hazard_ The river Simme flows along an embankment through Lenk im Simmental from Plaine Morte (Dead Plain), a glacier situated at the height of up to 2,840 meters above sea level In the Bernese Alps… Its glacial lake drained spontaneously in 2018 and caused flooding in the village. Photo Radhiyya Indra.

For people who live near the Swiss Alps, life is quiet and serene. This is especially true for the 300 or so inhabitants of a tiny village called Blatten in Valais, a canton in southern Switzerland.

But few among the village residents, let alone even scientists, could have predicted that their lives would be rocked by a sudden glacier avalanche.

That disaster in late May has continued to draw scrutiny of the unpredictable nature of glaciers and the impact of climate change across the globe.

On May 28, residents of Blatten watched from a distance as the Birch Glacier collapsed, engulfing their alpine village in a nearly unprecedented disaster. While Swiss authorities had managed to evacuate most of the residents a few days earlier, one elderly villager who reportedly left the evacuation zone was killed.

In the aftermath of the cataclysmic disaster, the village of Blatten was no more, leaving the surviving residents displaced.

The glacier avalanche that occurred in Switzerland’s heavily monitored mountainous region shocked experts worldwide and raised questions about why it escaped forecasts.

“All the people I talked to, glaciologists, everyone said they couldn’t predict this kind of event,” Luigi Jorio, a journalist with international news outlet SWI swissinfo.ch who has covered the environment for over 15 years, told The Jakarta Post early in June.

“All [Swiss] glaciers, including Birch, are monitored by cameras and satellites. But nobody really saw the mountaintop in Blatten coming down,” he added.

Glaciologists, including Christophe Lambiel at the University of Lausanne, have been cautious about specifying what particular factor contributed to the natural disaster that buried Blatten, noting its “complex” circumstances.

“There was this slow slide in the mountain that accelerated dramatically, which provoked several rockfalls on the glacier that pressured the glacier to eventually collapse,” Lambiel explained.

He added that the glacier’s unusual movement also played a role in the disaster.

Still, Lambiel did not rule out the possibility that climate change had contributed to the degrading permafrost, which in turn triggered the rockslide.

“The glaciers in Switzerland have been melting at a faster rate […] which [has] increased during the last 20 years and strongly accelerated in the past three years,” Lambiel said.

Among researchers, climate change continues to pop up as one of the potential causes for the unexpected movement of glaciers.

“The fact that those stones kept falling in the last five years or so showed some link to the changing of the climate,” said Daniel Farinotti, a glaciologist with the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich.

The Blatten glacier collapse has served as a wake-up call for both experts and policymakers, including Christophe Clivaz, a National Council member from Swiss environmentalist party Les Verts.

National concern_ Switzerland’s National Council member Christophe Clivaz interviewed by Radhiyya Indra in Bern. Photo Dorian Burkhalter.

For Clivaz, the disaster underlined the urgency for better mitigation efforts to prevent potential calamities that stem from warming global temperatures.

“[Climate change] is clearly an issue, and despite our good monitoring system, we must monitor the glaciers more closely in the next decades,” he said.

“But for me, the first priority now is to have more [government] funds to help and protect the population in the Alps against these disasters.”

Threat from above

Switzerland’s experience with glacier-related disasters, as well as potential risks from glacier hazards, is not limited to Blatten.

In 2018, Lac des Faverges, a glacial lake above the village of Lenk im Simmental, suddenly drained and sent more than 2 million cubic meters of floodwaters downstream, destroying infrastructure and damaging homes.

The impacts from this disaster, known as a glacial lake outburst flood (GLOF), was largely averted thanks to early warning systems that allowed people to evacuate early.

The village responded by building a drainage canal and installing temperature sensors to anticipate any future rise in the glacial lake’s water levels, according to Lenk Mayor Rene Mueller, a former chief of the local fire station.

“Since the 2018 disaster, we have weekly assessments. We look at the water levels in the Plaine Morte Glacier, its melting rates, and prepare accordingly,” he said.

However, the threat of other GLOFs looms on the horizon.

A 2023 study published in the international journal Nature Communications found that more than 700,000 people lived in areas of Switzerland at risk of potential glacier disasters.

Mueller understands this risk well, even though he lives in Lenk, one of the country’s most disaster-ready villages.

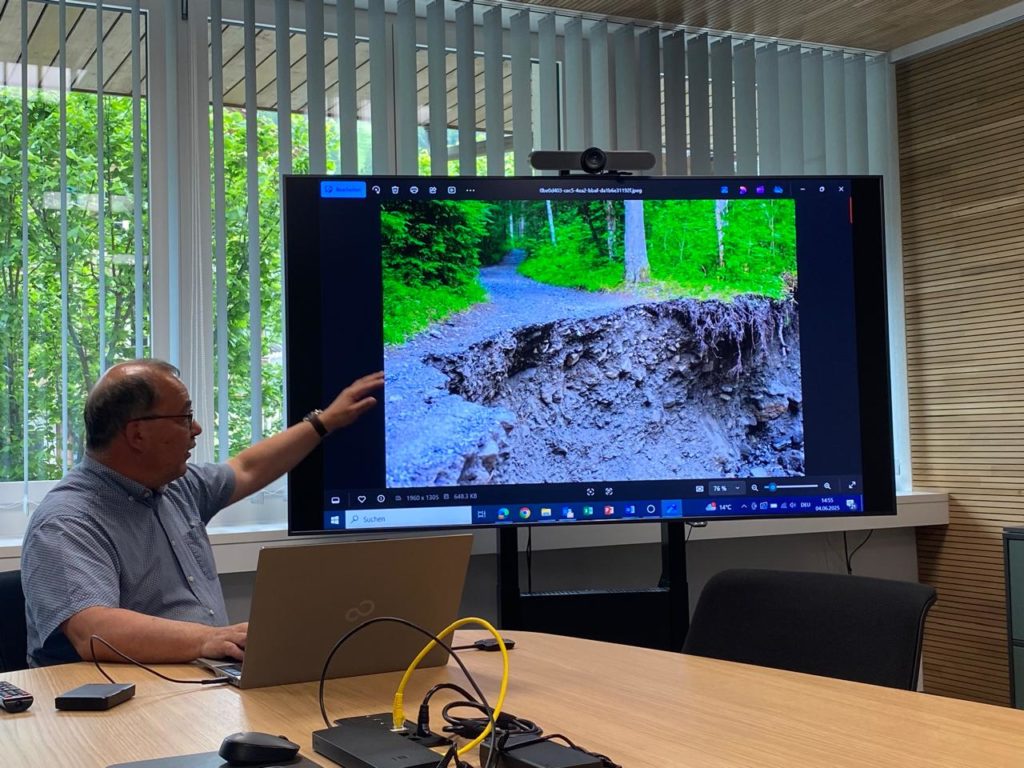

Natural impact_ Rene Mueller, the mayor of Lenk im Simmental, presents pictorial documentation of the massive infrastructural damage caused by the2018 glacial lake outburst flood. Photo Radhiyya Indra.

“Even though we’ve done everything we can, you can never be 100 percent sure,” the mayor said.

Scientists say glacier-related disasters remain hard to forecast.

Farinotti said that despite the high number of monitored sites in Switzerland, accurately predicting when a glacier collapse might occur was almost impossible.

“We could tell you which glaciers most likely pose an issue, but we could never tell in advance if it would cause a disaster. We just don’t have the knowledge,” he said.

“You usually [get the data] after the disaster has already happened.”

Global implications

While Switzerland has the resources and infrastructure to track glacier hazards in real-time, glaciologists worry that other countries may not be as well-equipped.

“Switzerland is a small, wealthy country,” Farinotti said.

“If you have villages living under glaciers in places like Chile, India or Indonesia, […] implementing a similar system takes financial means,” he noted.

Retno Marsudi, the former foreign minister who is now the Special Envoy of the United Nations Secretary-General on Water, said the Blatten disaster should serve as a reminder for other countries with mountain glaciers to consider the long-term effects of climate change.

This includes Indonesia, which is home to one of the few tropical glaciers in the world: the Carstensz Glaciers, which sit near the peak of Puncak Jaya in Central Papua and are at risk of disappearing. Local authorities report that the glaciers, known locally as “salju abadi” (eternal snow), are melting rapidly due to climate change and are predicted to vanish as early as 2026.

“First, [we need to] strengthen climate actions, because through robust climate actions, we can ensure strong adaptation and mitigation of the impacts of global warming,” she told the Post.

“This is the only option to preserve our glaciers. We must act now,” added Retno, who made the same suggestion during the first International Conference of Glaciers’ Preservation in Dushanbe, Tajikistan.

Incidentally, the three-day forum opened on May 29, the day after the Blatten disaster.

Amid the danger to glaciers worldwide, many Swiss residents still hope that experts will know how to mitigate related disasters better next time, despite lingering doubts.

One such person is William, a 68-year-old shopkeeper in Lenk, who preferred to provide only his first name.

“I can only hope the 2018 disaster will not happen again,” he said.

“But to be completely honest, I don’t know.”